Comment from the architect

This work for the Kunst Museum Winterthur was created on the basis of an open competition, which was won in 2020 by the architect Heike Hanada in collaboration with the artist Ayşe Erkmen. Read the commentary by Berlin architect Heike Hanada here.

Kunst Museum Winterthur | Reinhart am Stadtgarten

Foto: Georg Aerni

The aim was to create a permanent spatial installation in the form of an artistic reworking of the foyer and its main entrances. What was new about this process was the precondition of forming an interdisciplinary team from art and architecture. The boundary between the two disciplines is therefore fluid.

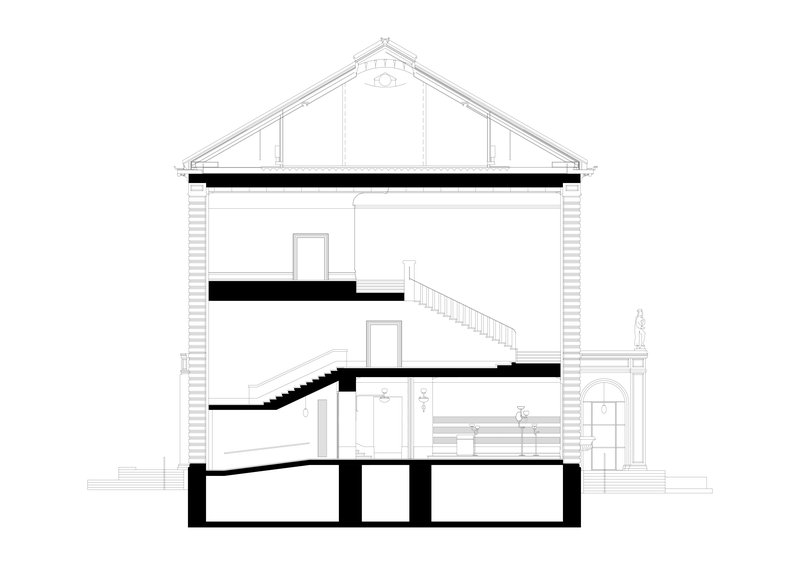

As a result, a project was developed that extends from the foyer from the inside to the outside and from the bottom to the top. Instead of developing an urban planning idea or an overall concept for the monument, as is generally the case, the spatial concept gradually determined the adjacent spatial layers starting from the central interior. The result was a composition of stairs and steps made of in-situ concrete, which was laid across or parallel to the building - similar to a baroque stage set - in the existing structure. This arrangement formed the basis for all further interventions.

Eingangshalle des Kunst Museum Winterthur | Reinhart am Stadtgarten. Foto: Andrew Alberts

The resulting block-like concrete objects are superimposed on existing staircases in the exterior and interior and form a monolithic layer of stone on top. No joints are recognizable in the material. The only necessary breaks are deliberately placed, striking distances from the existing building. In the foyer, the museum's formerly additive, strictly axially symmetrical spatial concept has been transformed into the horizontal layering of a fragmented landscape. The space expands. It liberates itself.

Betonelement in der Eingangshalle. Foto: Andrew Alberts

The originally neoclassical building was built in 1842 as a boys' school. At the beginning of the 20th century, it underwent several conversions. During the Second World War, the collector Oskar Reinhart began extensive renovations, which resulted in a completely new room structure and a new staircase. The museum was opened in 1951. Since then, the different layers of time inside and outside have been visible to the attentive observer. However, they can have an irritating effect. Oskar Reinhart's historicizing signature, but also the subsequent renovations, led to an unmistakable alienation. The independent concept of the museum as an oversized bourgeois living room for Oskar Reinhart's art collection could no longer be transported into the present day.

What remains, however, are the traces of the walls in the exhibition rooms with a pale blue-white tone, the dominant wood paneling and a radiant light that brightens everything up. What remains in the foyer are the carefully scratched and bush-hammered natural stone floors in dialog with layers of in-situ concrete, also bush-hammered. What cannot be experienced at first glance, but is essential, are the adapted, raised door lintels, which support the moment of openness. Additional directions of movement, in which the foyer now stretches in all four directions simultaneously, make the space appear light and less hierarchical.

While the lines of the steel shelves hovering above the floor point into the distance, the almost magnificent light objects by Koenraad Dedobbeleer provide a deliberate counterpoint to the otherwise straightforward horizontality of the room.

Querschnitt Kunst Museum Winterthur Reinhart am Stadtgarten © Heike Hanada

All the changes and superimpositions that the house undergoes with minimal measures are based on the idea of a scenic landscape. This is led through the house from the city garden to the city and vice versa. Its stone fragments manifest themselves in the interior and exterior spaces. As artefacts, they seek to harmonize the given and the new, starting from the ground. Each of these blocks can be used as a staircase, ramp, table or bench and yet at the same time become part of a romantic landscape in the eye of the beholder. Seen from a distance, the slowly rising steps nestle against the high wall of the house. The wall holds. It forms the background for new urban scenes. In the middle, the concrete breaks through the wall. Urban life makes its entrance.

Heike Hanada, artist and architect